“Borg” insects – mini spies of the future?

Insects’ agility in flight is unmatched. It’s been an inspiration to many inventors as in inventing helicopters or other flying machines. Instead creating robots which resemble insects, a few groups of engineers decided to develop technology which controls insects. An unquestioned fact is that nature developed the insects far better than humans are trying to mimic while building robots which resemble animals (if nothing else it had far more time). This article will cover two projects which are funded by DARPA.

Insects’ agility in flight is unmatched. It’s been an inspiration to many inventors as in inventing helicopters or other flying machines. Instead creating robots which resemble insects, a few groups of engineers decided to develop technology which controls insects. An unquestioned fact is that nature developed the insects far better than humans are trying to mimic while building robots which resemble animals (if nothing else it had far more time). This article will cover two projects which are funded by DARPA.

The Hybrid Insect Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems project (HI-MEMS), led by Amit Lal, aims to miniaturize all the technology necessary so that it fits within the body of a flying insect.

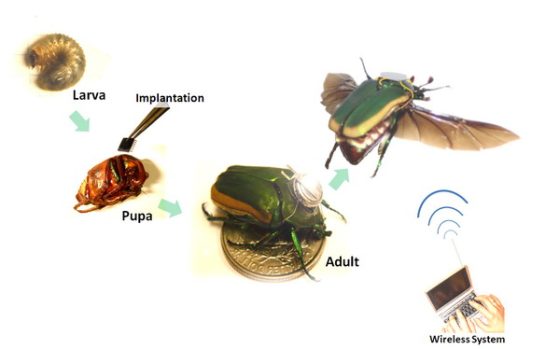

During their development from larvae to adults, most winged insects, including moths and beetles, undergo metamorphosis in a pupa stage, during which enzymes dissolve much of the larval tissue and the insect is rebuilt. The HI-MEMS project aims to merge artificial control systems with those of the insect by inserting the devices during the pupa stage. The idea is that as new organs and tissue develop, they will create strong, stable connections between the devices and the insects’ neural or muscular tissues. The control devices become part of the adult insect’s body.

The implants must be small and light enough not to interfere with the adult insect, and must reliably contact the neurons that control flight. HI-MEMS researchers have fabricated ultra-thin neural probes – a few hundred of micrometers across – out of flexible plastic, with traces of metal completing the electrical connections.

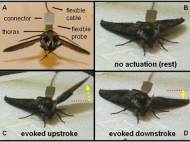

In a series of video clips shown at the conference and posted online, a tobacco hawk-moth with wires connected to its back lifts and lowers one of the wings or both, as a response to signals delivered to its flight muscles. As the researchers ramp up the frequency of the muscle stimulation, the moth’s wings beat faster, approaching take-off speed. In another clip, the moth is flying, tethered from above, when electrical impulses applied to muscles on one side or the other cause the moth to yaw left or right.

The flexible plastic probes should be inserted into tobacco hawk-moth pupae seven days before the moths emerged. They found that inserting them any earlier meant the tissue was too fluid to seal around the probe, but any later and development was too advanced and the probes damaged the moths’ muscles. A probe is embedded in each set of flight muscles on either side of the moth and a connection protrudes from the moth’s back. This can be hooked up to the joint wires which also deliver control signals and power. According to their paper, the team has also designed and built a battery-powered onboard control system, though there was no mention of whether they had made moths fly using this non jointed arrangement.

Another DARPA-funded group, led by Michel Maharbiz at the UC Berkeley, implanted electrodes into the brains of adult green June beetles, near neurons that control flight. When the team delivered pulses of negative voltage to the brain, the beetles’ wing muscles began beating and the bugs took off. A pulse of positive voltage shut the wings down, stopping flight short, and by rapidly switching between these signals, they controlled the insects’ thrust and lift. Maharbiz’s team found two ways to make tethered beetles turn. In one, they mounted an LED display in front of a beetle’s eyes. Lighting up the left or right portion turned the beetle in the opposite direction. In a second, more successful, approach they directly stimulated the flight muscles on one side, causing the insect to turn to the other.

Their system uses a battery glued to the outside of the beetle for power, while Lal’s moth-control system relies on power provided through wires plugged into the implant. Both would stick out like sore thumbs, and that’s before adding the microphones, environmental sensors and transmitters that they would need to be of any use as spies.

Research of animal-cyborgs has delivered results that have intrigued researchers in other fields. It also raised the awareness of paranoid individuals which from now have another object to worry about. There is also the question of ethics and moral. You can claim the equipment is light and that it doesn’t bother the insect, however, implanting stimulators on other species is widely disapproved by society – it has been done on other animals before and most of those projects are (officially) shut down.

Leave your response!