Clostridium sporogenes bacteria could aid in fight against solid tumors

A group of researchers from the University of Nottingham and the University of Maastricht have succeeded to employ a bacterium that is widespread in soil in order to fight cancer. They managed to modify a bacterial strain to specifically targets tumors without harming healthy tissue, and it could be used as a vehicle to deliver drugs in near future frontline cancer therapy.

A group of researchers from the University of Nottingham and the University of Maastricht have succeeded to employ a bacterium that is widespread in soil in order to fight cancer. They managed to modify a bacterial strain to specifically targets tumors without harming healthy tissue, and it could be used as a vehicle to deliver drugs in near future frontline cancer therapy.

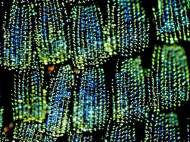

“Clostridia are an ancient group of bacteria that evolved on the planet before it had an oxygen-rich atmosphere and so they thrive in low oxygen conditions. When Clostridia spores are injected into a cancer patient, they will only grow in oxygen-depleted environments, i.e. the centre of solid tumors. This is a totally natural phenomenon, which requires no fundamental alterations and is exquisitely specific. We can exploit this specificity to kill tumor cells but leave healthy tissue unscathed”, said Professor Nigel Minton, Professor of Applied Molecular Microbiology at the University of Nottingham and leader of the research.

The Clostridium sporogenes bacterium is anaerobic, which means that it does not require oxygen to live and multiply. This bacterium is associated with a foul odor, and typically occurs in gangrenous infections. Spores of Clostridium sporogenes can grow within tumors where there is no oxygen (including solid tumors of the breast, brain and prostate) though not tumors in other tissues of the body where oxygen is present.

Spores of the bacterium are injected into patients and only grow in solid tumors, where a specific bacterial enzyme is produced. An anti-cancer drug is injected separately into the patient in an inactive ‘pro-drug’ form. When the pro-drug reaches the site of the tumor, the bacterial enzyme activates the drug, allowing it to destroy only the cells in its vicinity – the tumor cells.

“This therapy will kill all types of tumor cell. The treatment is superior to a surgical procedure, especially for patients at high risk or with difficult tumor locations”, said Professor Minton. “A successful outcome could lead to its adoption as a frontline therapy for treating solid tumors. If the approach is successfully combined with more traditional approaches this could increase our chance of winning the battle against cancerous tumors.”

They managed to overcome the hurdles that have prevented this therapy from entering clinical trials by introducing a gene for a much-improved version of the enzyme into the C. sporogenes DNA. The improved enzyme can now be produced in far greater quantities in the tumor than previous versions, and is more efficient at converting the pro-drug into its active form.

The strain is expected to be tested in clinical trials by cancer patients in 2013, and it will be led by researchers from the University of Maastricht in Netherlands.

Leave your response!