Pine cones inspire new materials that change their shape according to stimuli

Inspired by the ability of pine cones to close their scales when wet and open them again once they have dried out, a group of researchers at ETH Zurich devised a new method to produce a variety of composite materials that are able to change their shape to a pre-programmed shape after being influence by external stimuli. The findings could lead to improvements in material science and medicine.

Inspired by the ability of pine cones to close their scales when wet and open them again once they have dried out, a group of researchers at ETH Zurich devised a new method to produce a variety of composite materials that are able to change their shape to a pre-programmed shape after being influence by external stimuli. The findings could lead to improvements in material science and medicine.

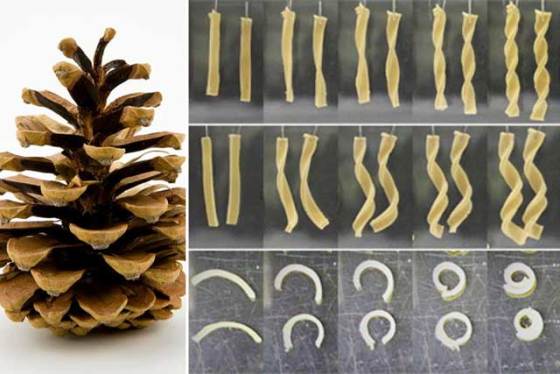

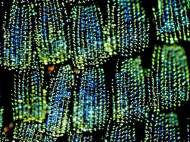

Pine cone scales consist out of two layers lying on top of each other. Although both layers consist of the same swellable material, they expand in different ways under the influence of water because of the rigid fibers enclosed in the layers. In each of the layers, these are specifically aligned, thus determining the direction of expansion.

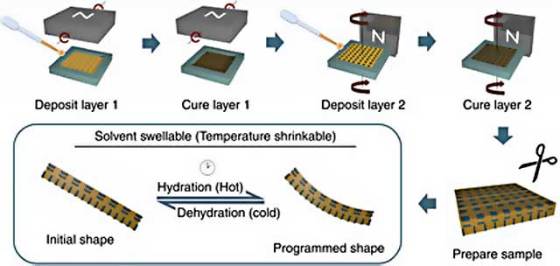

André Studart, a professor of complex materials at ETH Zurich’s Department of Materials, and his group used this phenomenon as inspiration to develop a material by adding ultrafine aluminum oxide platelets as the rigid component to gelatin – the swellable base material – and pouring it into square moulds. The surface of the aluminum oxide platelets is pre-coated with iron oxide nanoparticles to make them magnetic.

This enabled the researchers to align the platelets in the desired direction using a very weak rotating magnetic field. On the cooled and hardened first layer, they poured a second one with the same composition, differing only in the direction of the rigid elements.

This double-layered material is cut into strips, and depending on the direction in which these strips were cut compared to the direction of the rigid elements in the gelatin pieces, the strips bent or twisted differently under the influence of moisture. The researchers managed to fairly accurately make these strips take desired shape. While some coiled lengthwise like a pig’s tail, others turned loosely or very tightly on their own axis to form a helix reminiscent of spiral pastries.

The researchers also produced longer strips that behave differently in different sections – curl in the first section, for instance, then bend in one direction and the other in the final section. Or they created strips that expanded differently length and breadthwise in different sections in water. And they also made strips from another polymer that responded to both temperature and moisture – with rotations in different directions.

This phenomenon was previously used in thermostats where two metallic compounds bend upon temperature changes. The new method, however, is material-independent, which means that it can be applied to any material that responds to external stimuli.

According to ETH Zurich researchers, they plan two completely different directions in further development of this method. One is the production of ceramic parts that, instead of being pressed into shape as they have been until now, bring themselves into shape. The other direction could lead to biodegradable implants that take their final shape once they are in their definitive location in the body.

For more information, read the article published in Nature Communications: “Self-shaping composites with programmable bioinspired microstructures”.

Leave your response!