Researchers pinpoint how some plants fix nitrogen while others do not

Most of legume species, plants in the family Fabaceae (Leguminosae), live in symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria (rhizobia bacteria). The bacteria receive food from plant, and in turn the bacteria fix the nitrogen that most plants need to grow green and healthy. Researchers at the University of Missouri have found that nonlegumes plants respond to the same signal molecules as legume species. This discovery could help crops use less nitrogen fertilizer, benefiting both farmers and the environment.

Most of legume species, plants in the family Fabaceae (Leguminosae), live in symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria (rhizobia bacteria). The bacteria receive food from plant, and in turn the bacteria fix the nitrogen that most plants need to grow green and healthy. Researchers at the University of Missouri have found that nonlegumes plants respond to the same signal molecules as legume species. This discovery could help crops use less nitrogen fertilizer, benefiting both farmers and the environment.

Legumes are often used as a rotation crop to naturally enhance the nitrogen content of soils. Nitrogen fertilizers are also used to enhance the nitrogen level. In order to create the fertilizer, fossil fuels are combined with nitrogen from the atmosphere. When applied to crop fields, the excess fertilizer also ends up in rivers and streams, contributing to nitrification and hypoxia in waterways.

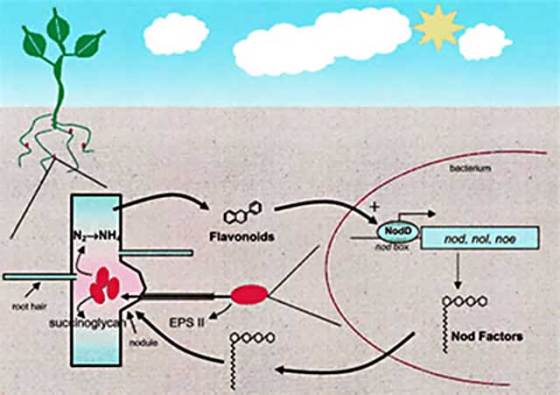

Signal molecules are extremely important to plants. They gather information about insects, bacteria and other threats and stresses from signal molecules. When legumes sense signals from rhizobia bacteria, they create nodules where the bacteria reside and receive food from the plant.

Nodulation (NOD) factors are signaling molecules produced by rhizobia bacteria during the creation of nodules on the root of legumes. This molecule is lipo-chitin, a sugar polymer with a fatty acid attached. It is similar to chitin normally found in the cell walls of fungi, the exoskeletons of crustaceans or insects.

Legumes respond to NOD factors by suppressing the innate immune response, which normally protects plants from pathogens. Hence, the bacteria stand a better chance of infecting and living inside the plant. The research team treated corn, soybeans, tomatoes and Arabidopsis to see how they responded when exposed to the chemical signals from the rhizobia bacteria.

Plants were treated with bacterial flagellin, a protein known to cause a strong immune response, and also received doses of the NOD factor. Researchers have found that all plants recognized the NOD factor which suppressed the plant’s immune response by 60 percent.

“After these results, what allowed us to take the next step forward is that we were able to make mutant plants with changes in what we think is the receptor for the NOD factor. That step showed that when plants lack the ability to recognize the NOD factor, you don’t see the suppression of the immune system”, said Gary Stacey, University of Missouri Bond Life Sciences Center (Bond LSC) investigator and plant sciences professor.

Although nonlegume species recognized the NOD factor, they didn’t complete the extra step of forming nodules to allow the bacteria to thrive. According to the Bond LSC researchers, these plants activated a different mechanism.

“Our next step is to determine how we can make the plants understand that this is a beneficial relationship and get them to activate a different mechanism that will produce the nodules that attract the bacteria instead of trying to fight them”, said Stacey.

For more information, read the paper published in the journal Science: “Nonlegumes Respond to Rhizobial Nod Factors by Suppressing the Innate Immune Response”.

Leave your response!