Robo Raven successfully performs bird-like flight

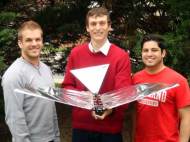

Researchers at the University of Maryland have developed and demonstrated a new flying robot which flaps its wings completely independently of each other. Dubbed Robo Raven, the robot can be programmed to perform any desired motion, enabling the bird to perform aerobatic maneuvers. This is the first time a robotic bird with these capabilities has been built and successfully flown.

Researchers at the University of Maryland have developed and demonstrated a new flying robot which flaps its wings completely independently of each other. Dubbed Robo Raven, the robot can be programmed to perform any desired motion, enabling the bird to perform aerobatic maneuvers. This is the first time a robotic bird with these capabilities has been built and successfully flown.

S. K. Gupta, a professor in Mechanical Engineering and the Institute for Systems Research in the A. James Clark School of Engineering, has been working on flapping-wing robotic birds for the better part of a decade. He and his graduate students, along with Mechanical Engineering Professor Hugh Bruck, demonstrated a flapping-wing bird back in 2007. This bird used one motor to flap both wings together in simple motions.

By 2010, the design had evolved over four successive models. The final bird in the series was able to carry a tiny video camera, could be launched from a ground robot, and could fly in winds up to 10 mph – important breakthroughs for robotic micro aerial vehicles that could be used for reconnaissance and surveillance.

In 2012, Gupta partnered with Bruck and their graduate students to retry the development of a robot with two independently flapping wings. Robo Raven has two programmable motors that can be synchronized electronically to coordinate motion between the wings. The problems needed to be solved were the two actuators required which required a bigger battery and an on-board micro controller, which initially made Robo Raven too heavy to fly.

In order to lower its weight, the team employed advanced manufacturing processes such as 3D printing and laser cutting to create lightweight polymer parts. Lowering weight was only a part of the solution, because they also programmed motion profiles that ensured wings maintained optimal velocity while flapping to achieve the right balance between lift and thrust.

University of Maryland researchers developed a way to measure aerodynamic forces generated during the flapping cycle, enabling them to evaluate a range of wing designs and quickly select the best one. Finally, the team performed system-level optimization to make sure all components worked well together and provided peak performance as an integrated system.

“We can now program any desired motion patterns for the wings”, Gupta said in his blog. “This allows us to try new in-flight aerobatics – like diving and rolling – that would have not been possible before, and brings us a big step closer to faithfully reproducing the way real birds fly.”

Leave your response!