Robots which feel – robot Kismet

Sociable humanoid robots pose a dramatic and intriguing shift in the way one thinks about control of autonomous robots. A new range of application domains are driving the development of robots that can interact and cooperate with people, and play a part in our daily lives. One of the pioneers in the mentioned domain was Kismet, a robot developed by Cynthia Breazeal in the late 1990s.

Sociable humanoid robots pose a dramatic and intriguing shift in the way one thinks about control of autonomous robots. A new range of application domains are driving the development of robots that can interact and cooperate with people, and play a part in our daily lives. One of the pioneers in the mentioned domain was Kismet, a robot developed by Cynthia Breazeal in the late 1990s.

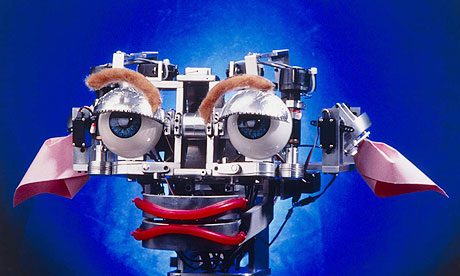

Kismet is an expressive robotic head, remarkably looking like a gremlin from a 1984 movie Gremlins. It is equipped with perceptual and motor modalities made to match common human communication skills. To facilitate a natural infant-caretaker interaction, the robot is equipped with visual, auditory, and proprioceptive sensory inputs. The motor outputs include vocalizations, facial expressions, and motor capabilities to adjust the gaze direction of the eyes and the orientation of the head. Note that these motor systems serve to steer the visual and auditory sensors to the source of the stimulus and can also be used to display communicative cues such as reactions to too fast visual stimulations or objects which are too far or too close.

The robot’s vision system consists of four color CCD cameras mounted on a stereo active vision head. Two wide field of view (fov) cameras are mounted centrally and move with respect to the head. These are 0.25 inch CCD lipstick cameras with 2.2 mm lenses manufactured by Elmo Corporation. They are used to decide what the robot should pay attention to, and to compute a distance estimate. There is also a camera mounted within the pupil of each eye. These are 0.5 inch CCD foveal cameras with an 8 mm focal length lenses, and are used for higher resolution post-attentional processing, such as eye detection.

Kismet has three degrees of freedom (DoF) to control gaze direction and three degrees of freedom to control its neck. The degrees of freedom are driven by Maxon DC servo motors with high resolution optical encoders for accurate position control. This gives the robot the ability to move and orient its eyes like a human, engaging in a variety of human visual behaviors. This is not only advantageous from a visual processing perspective, but humans attribute a communicative value to these eye movements as well.

The caregiver can influence the robot’s behavior through speech by wearing a small wireless microphone. This auditory signal is fed into a 500 MHz PC running Linux. The real-time, low-level speech processing and recognition software was developed at MIT by the Spoken Language Systems Group. These auditory features are sent to a dual 450 mHz PC running NT. The NT machine processes these features in real-time to recognize the spoken affective intent of the caregiver.

Kismet has a 15 DoF face that displays a wide assortment of facial expressions to mirror its “emotional” state as well as to serve other communicative purposes. Each ear has two degrees of freedom that allows Kismet to perk its ears in an interested fashion, or fold them back in a manner evocative of an angry animal. Each eyebrow can lower and furrow in frustration, elevate upwards for surprise, or slant the inner corner of the brow upwards for sadness. Each eyelid can open and close independently, allowing the robot to wink an eye or blink both. The robot has four lip actuators, one at each corner of the mouth, that can be curled upwards for a smile or downwards for a frown. There is also a single degree of freedom jaw.

The robot’s vocalization capabilities are generated through an articulatory synthesizer. The underlying software (DECtalk v4.5) is based on the Klatt synthesizer which models the physiological characteristics of the human vocal tract. By adjusting the parameters of the synthesizer it is possible to express speaker personality (Kismet sounds like a young child) as well as adding emotional qualities to synthesized speech.

Crucial to its drives are the behaviors that Kismet uses to keep its emotional balance. For example, when there are no visual cues to stimulate it, such as a face or toy, it will become increasingly sad and lonely and look for people to play with. Responding to Kismet restores its (emotional) stability, thus making it happy again. Similarly, if its caregiver continuously repeats the same gestures, such as shaking a doll in front of it, it will get bored and agitated.

There is going to be a robot apocalypse