Roomba senses owners emotions

This article combines two of our previous stories. The concept of controlling a robot using emotions instead of traditional controls is one of the emerging technologies which will help both humans and robots to interact more naturally. A group of researchers from Calgary University, Canada decided to explore the development of a robot that would react accordingly to the way a human feels instead of having to be told what to do.

This article combines two of our previous stories. The concept of controlling a robot using emotions instead of traditional controls is one of the emerging technologies which will help both humans and robots to interact more naturally. A group of researchers from Calgary University, Canada decided to explore the development of a robot that would react accordingly to the way a human feels instead of having to be told what to do.

Traditional robots and most computer systems rely on the use buttons, joysticks and other controls to operate. The prototype works with these too, but it also can be controlled using a headband that reads muscle tension in bioelectrical signals produced directly by the brain. Look ma, no hands! This muscle tension is used to approximate the human emotions of relaxation and stress, so that the robot knows to tune in when the user may want some alone time, move away and look busy.

A specially-equipped iRobot Roomba robot vacuum cleaner can now sense human emotions. Using an OCZ NIA headband to capture bioelectric signals from the forehead of a person, the system collects this data and then infers stress from muscle tension readings. Their control software (which displays live measurements for muscle tension, eye glancing as well as alpha and beta waves) reinterprets natural muscle tension as estimating the user’s stress level; the more muscle tension, the more stress is inferred.

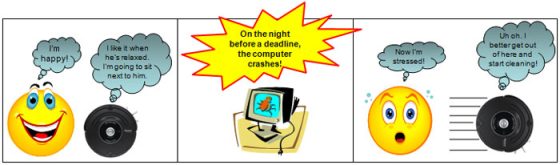

They constructed two methods allowing people to control the Roomba. The first was direct control, where a person controlled their bioelectrical signals to directly affect robot speed. The second was behavioral control, where a person’s emotional state was inferred based on their bio-electrical signal state, and the robot adjusted its behavior to fit that person’s emotional state.

Paul Saulnier, one of the researchers, said that at first the robot was controlled by somebody consciously changing the bioelectrical signals he or she sent out. The robot would change its speed with the clenching of a jaw or the tensing of an eyebrow, demonstrating that a link between the robot and the physical signs of stress was possible.

The next step was to create software that could read muscle tension, interpret it in terms of stress levels, and control Roomba accordingly. “When a person shows high stress (Levels 3 and 4), the robot enters its cleaning mode but moves away from the user so as not annoy them,” the team explains in its paper. “When a person is relaxed (Level 1), the robot (if cleaning) approaches the person and then stops, simulating a pet sitting next to its owner. If the reading is in between these two levels, the robot continues operating in its current mode until the stress reading reaches a threshold.”

The research in this field allows new breakthroughs in order that humanoid robots could be programmed to recognize stress and talk to their owners to calm or comfort them.

Leave your response!