Ancient Roman seawater concrete could teach us how to cut carbon emissions

In a quest to make concrete more durable and sustainable, an international team of geologists and engineers has found inspiration in the ancient Romans, whose massive concrete structures have withstood the elements for more than 2,000 years. The discovery could help improve the durability of modern concrete, which within 50 years often shows signs of degradation, particularly in ocean environments.

In a quest to make concrete more durable and sustainable, an international team of geologists and engineers has found inspiration in the ancient Romans, whose massive concrete structures have withstood the elements for more than 2,000 years. The discovery could help improve the durability of modern concrete, which within 50 years often shows signs of degradation, particularly in ocean environments.

The research team was led by Paulo Monteiro, a UC Berkeley professor of civil and environmental engineering and a faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), and Marie Jackson, a UC Berkeley research engineer in civil and environmental engineering. They characterized samples of Roman concrete taken from a breakwater in Pozzuoli Bay, near Naples, Italy.

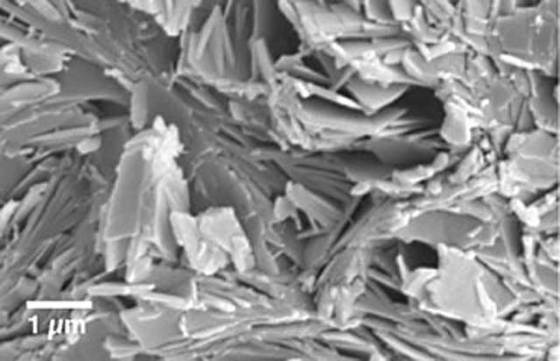

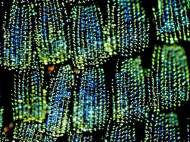

Using the Advanced Light Source at Berkeley Lab, a research team from the University of California, Berkeley, examined the fine-scale structure of Roman concrete. The findings revealed how the extraordinarily stable compound – calcium-aluminum-silicate-hydrate (C-A-S-H) – binds the material used to build some of the most enduring structures in Western civilization.

The manufacturing of Roman concrete also leaves a smaller carbon footprint than does its modern counterpart. The process for creating Portland cement, a key ingredient in modern concrete, requires fossil fuels to burn calcium carbonate (limestone) and clays at about 1,450°C (2,642°F). Seven percent of annual global carbon dioxide emissions originate from this activity.

The production of lime for Roman concrete, however, is much cleaner, requiring temperatures that are two-thirds of that required for making Portland cement. The researchers also found a very rare hydrothermal mineral called aluminum tobermorite (Al-tobermorite) that formed in the concrete. Integration of the results from the various beamlines revealed the minerals’ potential applications for high-performance concretes, including the encapsulation of hazardous wastes.

The recipe for Roman concrete was described around 30 B.C. by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, an engineer for Octavian, who became Emperor Augustus. The not-so-secret ingredient is volcanic ash, which Romans combined with lime to form mortar. They packed this mortar and rock chunks into wooden molds immersed in seawater. The seawater instantly triggered a hot chemical reaction. The lime was hydrated – incorporating water molecules into its structure – and reacted with the ash to cement the whole mixture together.

Rather than battle the marine elements, Romans harnessed saltwater and made it an integral part of the concrete – a goal that would cut greenhouse gas emissions and lead to stronger, longer-lasting buildings, bridges, and other structures.

While Roman concrete is durable, the UC Berkeley researchers claim it is unlikely to replace modern concrete because it is not ideal for construction where faster hardening is needed. However, the researchers are now searching for ways to apply their discoveries about Roman concrete to the development of more earth-friendly and durable modern concrete.

They are investigating whether volcanic ash would be a good, large-volume substitute in countries without easy access to fly ash, an industrial waste product from the burning of coal that is commonly used to produce more environmentally friendly concrete we mentioned in some of our green architecture articles.

Leave your response!