Magnetism observed in a gas for the first time

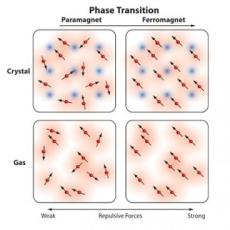

MIT scientists have been working on an answer for a decades-old question of whether it is possible for a gas to show properties similar to a magnet made of iron or nickel. Ferromagnetic materials are those that, below a specific temperature, are strongly magnetized even in the absence of a magnetic field. In common magnets such as iron and nickel that consist of a repeating crystal structure, ferromagnetism occurs when unpaired electrons within the material spontaneously align in the same direction.

MIT scientists have been working on an answer for a decades-old question of whether it is possible for a gas to show properties similar to a magnet made of iron or nickel. Ferromagnetic materials are those that, below a specific temperature, are strongly magnetized even in the absence of a magnetic field. In common magnets such as iron and nickel that consist of a repeating crystal structure, ferromagnetism occurs when unpaired electrons within the material spontaneously align in the same direction.

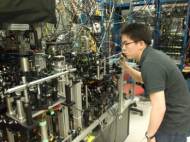

The MIT team observed the behavior in a gas of lithium atoms cooled to 150 billionth of 1 Kelvin above absolute zero (-273°C). The research was led by Wolfgang Ketterle, the John D. MacArthur Professor of Physics, and by David E. Pritchard, the Cecil and Ida Green Professor of Physics. If confirmed, the MIT result may enter the textbooks on magnetism, showing that a gas of elementary particles known as fermions does not need a crystalline structure to be ferromagnetic.

“All liquid or gaseous fermion systems in nature don’t have strong enough interactions to become ferromagnetic,” explains physics graduate student Gyu-Boong Jo, a member of the research team. “But for the lithium atoms, we can use tricks of atomic physics to adjust the interactions between the atoms to arbitrary strength, by simply changing an external magnetic field.”

In their experiment, the MIT team trapped a cloud of ultra-cold lithium atoms in the focus of an infrared laser beam. When they gradually increased the repulsive forces between the atoms, they observed several features indicating that the gas had become ferromagnetic. The cloud first became bigger and then suddenly shrunk. When the atoms were released from the trap, they suddenly expanded faster.

This and other observations agreed with theoretical predictions for a phase transition to a ferromagnetic state. “The evidence is pretty strong,” says Pritchard, “but it is not yet a slam dunk. They started to form molecules and may not have had enough time to develop regions of aligned atoms large enough for us to see.”

Ketterle adds that he and his colleagues have many ideas how to study this new form of matter more closely: “One thing is certain: We have made an important discovery, which will advance our understanding of magnetism.”

Christophe Salomon, research director at France’s National Center for Scientific Research, says the findings provide convincing evidence that fermionic gases display the same type of ferromagnetism found in solid crystal materials. To fully prove the case, he says, “It would be nice to see direct observation of ferromagnetism – that all the spins are parallel.”

The MIT research is part of a program studying new magnetic materials which have important applications in data storage, nanotechnology and medical diagnostics, as well as the interplay between magnetism and superconductivity.

The work is a continuation of earlier research on Bose-Einstein condensates, a form of matter in which particles condense and act as one big wave. Ketterle received the 2001 Nobel Prize for the discovery and study of this long-sought new form of matter. “We still use the same refrigerator as we used to study Bose-Einstein condensates,” says Ketterle. “But the science is very different. Ten years ago, I would have never thought that I would study magnetism today.”

Leave your response!