Ultra-sensitive polymer able to detect explosives

A team of chemists at the Cornell University developed a polymer that could be used to detect a chemical that’s often the key ingredient in improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The polymer, which could find its use in low-cost, handheld explosive detectors and could be used to replace bomb-sniffing dogs, can be quickly and safely detected in trace amounts of explosive substances.

A team of chemists at the Cornell University developed a polymer that could be used to detect a chemical that’s often the key ingredient in improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The polymer, which could find its use in low-cost, handheld explosive detectors and could be used to replace bomb-sniffing dogs, can be quickly and safely detected in trace amounts of explosive substances.

Research Department Explosive (RDX) is an explosive material common in military and industrial applications. However, it is also a favorite of bomb-making terrorists. It requires a detonator to explode, it is more powerful than TNT and its vapor pressure is 1,000 times lower than TNT’s – making it almost impossible to detect without direct contact like the swabs used at airport security.

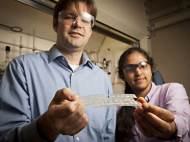

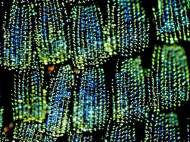

Invented in the lab of William Dichtel, assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology, the new material was discovered by accident. Dichtel’s general research interest is in two-dimensional polymers, which are extremely orderly in their molecular pattern. While attempting to discover a new two-dimensional polymer, Duchel and graduate student Deepti Gopalakrishnan found this new material, which does not have the same type of orderly structure, but turned out to be perfect for RDX detection.

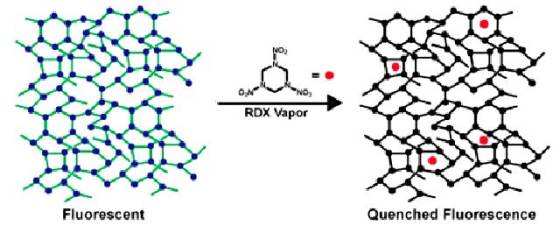

The researchers’ work relies on a previously established technology that uses “fluorescence quenching” as the basis for detecting TNT. The polymer has a random, cross-linked structure that allows it to absorb light and transport the resulting energy throughout its structure. After a certain period of time, the polymer releases this accumulated energy as light, a process known as fluorescence.

When it reacts in the presence of the explosive, the polymer’s fluorescence shuts off, thus allowing quick and accurate detection if RDX is present on a surface or in the air. This phenomenon occurs when accumulated energy encounters a molecule of explosive as it travels through the polymer, thus converting into heat rather than light and causing the polymer to stop glowing.

This design allows the polymer fluorescence to sense extremely small amounts of the explosive of interest, enabling identification of IEDs or people who have recently handled them. One of the goals Cornell researchers have set is to make detectors that can detect not just explosives on someone’s hands, but in the cloud around them thus allowing detection of explosives in bags without opening them.

The polymer network also responds to TNT and PETN similarly introduced from solution or the vapor phase. The researchers also experimented with other chemicals, such as those found in lipstick and sunscreen, to rule out false positives. Pure solvents, volatile amines, and the outgassed vapors from lipstick or sunscreen do not quench polymer fluorescence.

The established success of TNT sensors based on fluorescence quenching makes this a material of interest for real-world explosive sensors and will motivate further interest in cross-linked polymers and framework materials for sensing applications.

For more information, read the paper published in the Journal American Chemical Society: “Direct Detection of RDX Vapor Using a Conjugated Polymer Network”.

Leave your response!