Using paper to generate electrically conducting structures

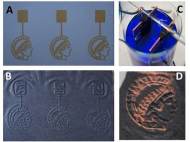

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces in Potsdam-Golm have created targeted conductive structures on paper. Their method relies on conventional inkjet printer which prints a catalyst on a sheet of paper. After getting heated, the printed areas on the paper get converted into conductive graphite. Being an inexpensive, light and flexible raw material, paper is therefore highly suitable for electronic components in everyday objects.

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces in Potsdam-Golm have created targeted conductive structures on paper. Their method relies on conventional inkjet printer which prints a catalyst on a sheet of paper. After getting heated, the printed areas on the paper get converted into conductive graphite. Being an inexpensive, light and flexible raw material, paper is therefore highly suitable for electronic components in everyday objects.

Researchers convert the cellulose of the paper into graphite with iron nitrate serving as the catalyst. If the researchers subsequently heat the sheets that were printed with a catalyst to 800°C (1,472°F) in a nitrogen atmosphere, the cellulose will continue to release water until all that remains is pure carbon. Whereas an electrically conducting mixture of regularly structured carbon sheets of graphite and iron carbide forms in the printed areas, the non-printed areas are left behind as carbon without a regular structure, and they are less conductive.

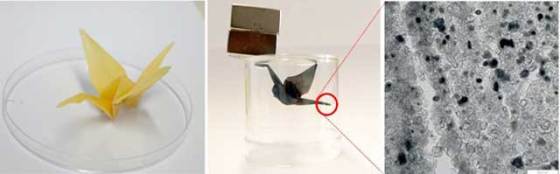

The team also managed to use their method in order to create 3D conductive structures. The team folded a sheet of paper into an origami crane which got immersed in the catalyst and baked into graphite. They used an origami bird and demonstrated the process by electrolytically coating it with copper. The entire crane subsequently had a copper sheen.

Researchers at Max Planck Institute managed to record the actual process of the catalytic conversion with transmission electron microscope. They managed to observe how the catalyst journeyed through the paper in the form of nano-droplets of an iron-carbon molten mixture, leaving graphite in its wake. Gathered information about graphite formation gave the researchers a comprehensive insight into catalytic conversion.

“Our study shows that molten metal, or a so-called eutectic, is formed”, said Cristina Giordano, who leads a working group at the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces. “We observed something interesting here, as iron itself does not melt until temperatures of about 1500 degrees are reached.”

Aside production of paper electronics, it may be possible to use this phenomenon for other applications such as manufacture of carbon nanotubes, where iron has been used as a catalyst for quite some time already.

Moreover, the Max Planck Institute researchers intend to further explore the potential of paper electronics and use the versatility of inkjet printer cartridges to use different cartridges that contain iron nitrate solutions, as well as solutions from other metal salts or dispersions containing metal particles finely distributed in water can be brought to paper.

For more information, read the paper published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition: “From Paper to Structured Carbon Electrodes by Inkjet Printing”.

Leave your response!