Using solar power to clean up industrial oxidation reactions

A group of researchers from Washington University in St. Louis came up with an idea to combine two existing technologies in order to clean up industrial oxidation reactions. They are using photovoltaic cells to power electrochemical reactions to eliminate the toxic byproducts of reactions commonly used in chemical synthesis — and with them the environmental and economic damage they cause.

A group of researchers from Washington University in St. Louis came up with an idea to combine two existing technologies in order to clean up industrial oxidation reactions. They are using photovoltaic cells to power electrochemical reactions to eliminate the toxic byproducts of reactions commonly used in chemical synthesis — and with them the environmental and economic damage they cause.

Led by Kevin Moeller, a professor of chemistry in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, the researchers used a $6 solar cell intended to power toy cars to run reactions and prove the concept. In an oxidation reaction, an electron is removed from a molecule. But that electron has to go somewhere, so every oxidation reaction is paired with a reduction reaction, where an electron is added to a second molecule.

“Electrochemistry can oxidize molecules with any oxidation potential, because the electrode voltage can be tuned or adjusted, or I can run the reaction in such a way that it adjusts itself”, said Moeller. Moreover, the byproduct of electrochemical oxidation is hydrogen gas.

On the other hand, electrochemistry can be only as green as the source of the electricity. If the oxidation reaction is running clean, but the electricity comes from a coal-fired plant, the problem has not been avoided, just displaced. Moeller’s group has been studying how solar-powered electrochemistry might be used to recycle chemical oxidants in a more environmentally friendly way.

“An electrode selects purely on oxidation potential”, said Moeller. “A chemical reagent does not. The binding properties of the chemical reagent might differ from one part of the molecule to another. And there’s also something called steric hindrance, which means that one part of the molecule might physically block access to an oxidation site, forcing substrates to other sites on the reagent.”

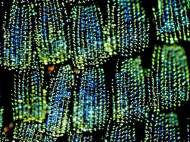

The reagents are usually expensive and toxic, so they are recycled. For example, an industrial alcohol oxidation uses the oxidant chromium to convert an alcohol into a ketone. In the process, the chromium picks up electrons and becomes chromium IV. Chromium IV is the waste product of the oxidation reaction and it is highly toxic. Sodium periodate is used to recycle the highly toxic chromium IV, but the restoration itself destroys three equivalents of periodate for every equivalent of desired product produced.

Chromium IV can be recycled electrochemically instead being recycled through a reaction with periodate. Instead of periodate waste, the reaction would produce hydrogen gas as the byproduct.

“Another example is an industrial process for carrying out alcohol oxidations that convert the alcohol group to a carbonyl group”, said Moeller. This process uses TEMPO, a complex chemical reagent discovered in 1960. TEMPO is expensive so it is recycled by the addition of bleach. This regenerates the TEMPO but produces sodium chloride as a byproduct.”

In small quantities sodium chloride is table salt, but in industrial quantities it is a waste product whose disposal is costly. Once again, the TEMPO can be recycled using electrochemistry, a process that produces hydrogen as the only byproduct.

“We can’t make all of chemical synthesis cleaner by hitching solar power to electrochemistry, but we can fix the oxidation reactions that people use. And maybe that will inspire someone else to come up with simple and innovative solutions to other types of reactions they’re interested in”, said Moeller.

For more information, you can read the article published in the journal Green Chemistry named: “Connecting the dots: using sunlight to drive electrochemical oxidations”.

Leave your response!